HR and Facility Management

Partnership, ownership or fusion?

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent changes to the world of work have had many impacts on organizations and the facility management profession. What started as an exercise in crisis management soon turned into a future gazing, strategic one, as organizations thought about the amount of real estate they needed, where that real estate should be and what that meant for future workspace provision.

And that was just the start. The ripple effect from these decisions appears to be endless. If workforce footfall is going to be unpredictable and less than smooth, how do organizations plan service provision? What is needed to clean the building as often and if not, how do organizations optimize that? For those suppliers who base their services on square foot measurements they will be concerned about a potential mass shedding of space, while having to come up with answers for the potentially existential questions being asked of them by their clients.

It is fair to say that this period in facility management history has the potential to be defining.

It has also been an emotional rollercoaster. During lockdowns, in crisis management mode, FMs were heralded as professionals that stepped up to the plate when it counted. Frontline staff finally received the recognition they deserved. FM had the limelight at last. But switching from reactive mode into the department that had to lead dramatic change was a sharp about turn, leaving many searching for answers looking to peer organizations for clues, and desperately trying to pool data sources together to develop a forward plan.

But they are not the only ones.

What the shift to hybrid working has highlighted is that this is not just an FM challenge. It is an organizational one, with other business functions wrestling with the same questions, albeit from slightly different vantage points. And one function at the heart of this challenge is human resources.

Many of the issues that hybrid working has created are people related. In an interview on the Workplace Geeks podcast, Jack Nilles, the father of teleworking/telecommuting, explained how in the mid 1970s, he and his team demonstrated that remote working not only worked but also had many benefits. Not least was the dramatic reduction in commuting traffic in cities that working in this way would create.

When asked why it was that it took a global pandemic for organizations to seriously consider remote working at scale his answer was direct: “Technology has never been the problem ... essentially management’s always been the problem.”

It was people management, part of organizational culture. The bread and butter of the HR community.

It follows then that HR also helped organizations navigate one of the biggest shifts in working practices since the industrial revolution. How do they ensure that new employees can be inducted with the right people when they are rarely in the same room together? How do they ensure that those that do come into the office do not put themselves first in the queue for promotions or other opportunities ahead of those that choose to work more remotely? How do employers manage a culture in manufacturing plants where line workers must come into the factory and take instruction from management working from home? How do organizations maintain a meritocracy when it is so easy to operate an out of sight, out of mind policy?

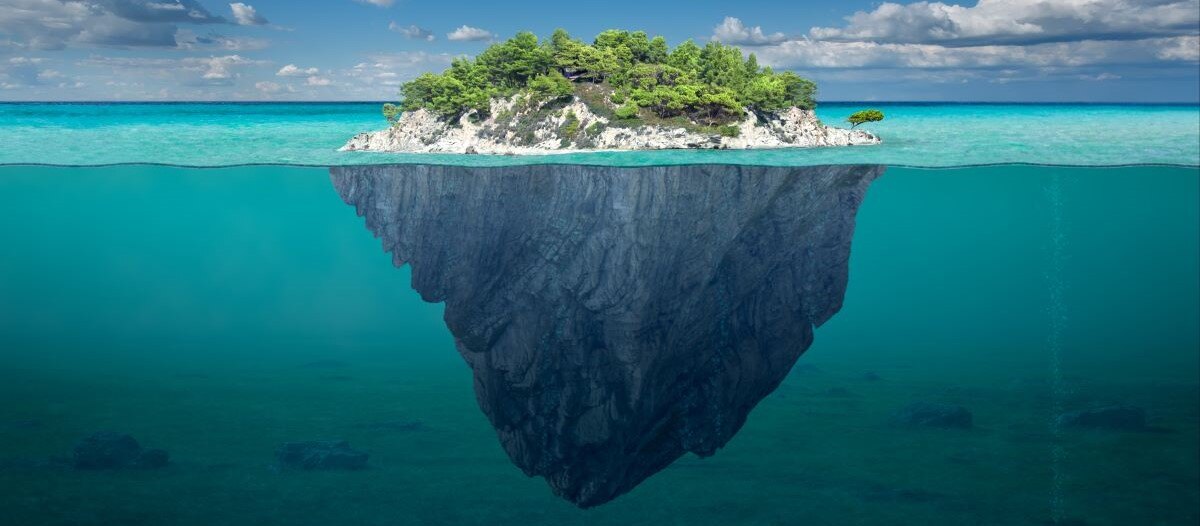

Many of these challenges, given the context is a new approach to the location of work, have a strong resonance with the challenges facing the FM community. In a vacuum, it can be difficult to spot other areas and departments wrestling with their issues. However, if departments can meet in the middle, they can recognize how often they face the same issues.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some FM and HR practitioners developed a closer understanding during the pandemic for this very reason, but it felt like the start of something that needed to be a far deeper bond.

FM and HR collaborating has been a topic of debate for decades but seems to have failed to make a real impact beyond the FM conference circuit for a few reasons. In 2015, in the UK, the Institute of Workplace and Facilities Management (IWFM) (formerly the British Institute of Facilities Management (BIFM)), launched its The Workplace Conversation campaign in partnership with the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), an international association for HR professionals.

The objective, as the name suggests, was to create a community conversation about how these two professional tribes could form a stronger bond, develop a mutual understanding and combine their strengths to transform how employees are enabled to work using both cultural and spatial management levers.

The initiative sadly failed to make the impact it had hoped for. There was plenty of interest from FMs in their quest for a more business relevant framing of their profession, but the engagement from the HR profession was minimal. Why? There could be many reasons, but it could suggest that building management was neither of interest nor an attractive proposition for the HR community to consider.

At the BIFM conference that year, when speaking about the findings, the question was asked “What can FM do with this now?”

The answer?

The concept of workplace management was going to become increasingly important, because employee power was only going to increase in line with every other part of experience-driven everyday lives. Because at that time, HR did not want to wrap its hands around the concepts it so FM should, with both hands. This was the opportunity to own, shape and lead on an emerging idea. FM just needed to take it.

Has it? Sort of. Slowly.

BIFM, three years later, took the bold move to change their name to incorporate the ‘W’ of workplace, while CIPD have carried on as they are – albeit with a token nod to (physical) workplace as part of the body of knowledge that HR professionals may be interested in.

But the pandemic may have renewed interest. Locations, and how often employees need to be in that location, have become critical when it comes to attracting and retaining talent. That, alongside how workspaces have themselves become a tool in bagging talent in a heavily competitive talent market, means that workplace experience is very much back on the agenda for HR professionals.

So, what does that mean for the future for HR and FM’s relationship? Is this about partnership, where the two departments work with each other, pooling resources, data, ideas and creating a shared language?

Or is it a race until one becomes the dominant voice of workplace matters, with the other being relegated to a subservient rung of the corporate ladder?

Or does something brand new emerge from this fusion of the two departments? With both professions finding themselves using 20th century tools to tackle 21st century problems, is it a case of now downing those tools, forgetting historic biases and starting to imagine what was once billed the chief workplace officer’s remit is about?

Perhaps, but there will be a lot of legacy and ego to navigate on that journey, which means whatever the future direction is, it will likely be a slow burn.

So, what can be done in a shorter timeframe?

How about gathering around a common idea, a common framework or even a common language? Could that be workplace experience?

FMs, HR and IT must recognize the word workplace means different things to different people. When FMs speak about it they are typically talking about workspace; when HR speaks on it, they are typically talking about the culture and benefits that impact the workforce; and those in IT could as easily be talking about the digital work environment.

There is already one major U.K. business that has used this framework to bring together FM, HR and IT, with each still retaining their own, identity and expertise, but all of them uniting around a single focus: creating amazing workplaces for people to do amazing work.

Perhaps it is not about departments combining, winning or evolving. Perhaps it is more important they remember why they all do what they do and who they do it for.

Chris Moriarty is co-founder and director of Audiem, a new workplace experience analytics platform that assesses workplace experience through written submissions from employees rather than agreement scales. He is also co-host of the Workplace Geeks podcast, a deep dive into some of the most progressive, innovative and defining academic papers around the broad workplace arena. He was previously director of insight at IWFM and U.K. MD for Leesman.

Read more on Communication , Occupancy & Human Factors and Workplace

Explore All FMJ Topics