Safety is More Than a Slogan

Turning the tide on preventable workplace fatalities

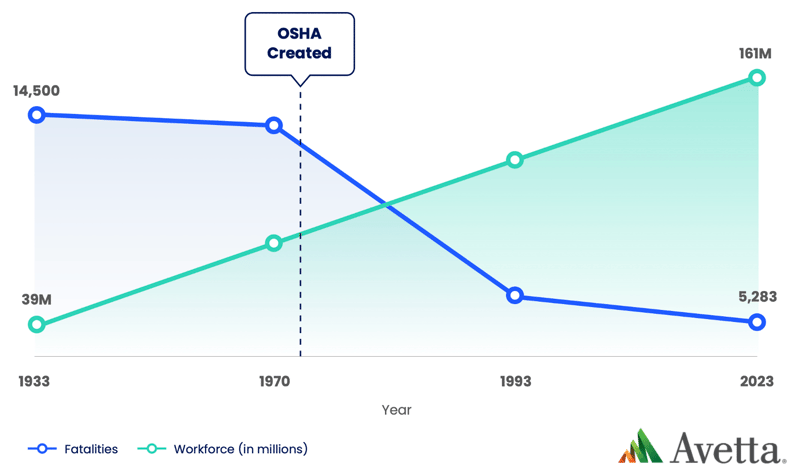

In 2023, 5,283 workers in the United States died on the job, according to the National Safety Council. That amounts to 14 workplace deaths every day while performing duties essential to the economy, their communities and their employers. The emotional impact of these losses on families, coworkers and communities is immeasurable.

Industrialized nations report similar workplace fatality patterns, particularly in sectors such as construction, transportation, manufacturing, and oil and gas. All told, the International Labor Organization reports 330,000 accidental global workplace deaths each year. Despite well-established regulatory bodies, safety protocols and increased awareness, the number of preventable fatalities has continued to persist in recent years.

A look back to move forward

For those unfamiliar with the history of workplace safety, today’s fatality numbers may be surprising. However, over time, significant safety improvements have often been preceded by catastrophic events that sparked long-overdue change.

Events such as the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, which killed 146 garment workers, brought unprecedented public attention to unsafe working conditions, leading to foundational changes in workplace safety laws and industrial regulations.

The introduction of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in 1970, followed by its enactment the following year, marked a significant turning point. Within two decades, the annual number of U.S. workplace fatalities fell significantly, from approximately 14,000 deaths in 1970 to 6,331 in 1993. This reduction is especially remarkable when one considers that the workforce increased from 79 million to 120 million workers during the same period.

However, by the early 2000s, progress began to slow down. Despite advances in training, equipment and reporting tools, the rate of fatal incidents plateaued. In some years, the number of deaths even increased slightly. Hyper-focus on regulatory-required reporting (OSHA Recordables, TRIR, etc.) has operated on the rather large assumption that if organizations drive down fatality frequency, they will also drive down severity. This is not working. The type of risk leading to serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs) is different and requires a targeted strategy to identify, prioritize and reduce the types of SIF risk leading to workplace fatalities.

To make meaningful progress, organizations need to go beyond what has already been done while strengthening foundational elements of compliance and taking a closer look at better practices.

The safety baseline: Critical in the modern world of work

As labor strategy shows an increasing dependence on third-parties — contractors, subcontractors and temporary labor — to accomplish an organization’s mission, it is imperative to have line of sight into who is in the work system; the type of work (risk) being performed; when it is being performed; and if the right teams, resources and capacity are in place to manage this type of risk. None of this occurs without a baseline strategy that serves to create this line of sight and enable planning while also satisfying the foundational elements of due-diligence — regulatory, compliance, insurance, contractual, etc. — that is so critical from an organizational risk standpoint.

Foundational elements such as a pre-qualifications process to establish the minimum conditions required to begin work coupled with safety program review and capabilities for safe work are part of this baseline. According to the Avetta Insights and Impact Report 2025, suppliers who completed prequalification programs achieved better safety outcomes than the industry average in terms of days away, restricted or transferred rate (DART) and lost workday case rate (LWCR).

Surprisingly, even suppliers who started prequalification processes but did not finish them still ended up with better safety records than the industry average. Just getting involved in safety prequalification processes, even without crossing the finish line, appears to make a significant positive impact.

Surprisingly, even suppliers who started prequalification processes but did not finish them still ended up with better safety records than the industry average. Just getting involved in safety prequalification processes, even without crossing the finish line, appears to make a significant positive impact.

Compliance is an important baseline, and while a systems approach can take organizations beyond the limitations of compliance, the benefits of standardized, uniform processes serve as both a means to set expectations as well as a filter for third-party employers performing work within a business environment.

Manual audits: Repetition with a purpose

Organizations that complete regular audits of suppliers’ safety processes over multiple years typically see stronger safety outcomes. These audits are not just about paperwork. They help leadership understand what is happening on the ground and create space for honest, practical improvements. Audits offer a chance to close the gap between “work as imagined” based on what is written in workplace policies and procedures and how “work is done” on the frontline, which often leads to recommendations for further, site-level risk reviews, leader-worker participation and engagement.

This is why tools that enable deeper insights into the systems- and risk-based capabilities of a contracted workforce are so important. For example, a scoring index can reveal the limitations of compliance alongside the safety systems capabilities. This allows organizations to understand where there are strengths and opportunities within their contractor management system, going beyond compliance and delivered in a way that promotes safety maturity within work systems as well as for contractors.

Credit health as a risk signal

Finally, as it turns out, a less common but nevertheless important factor is financial stability. Data shows that companies with deteriorating credit health correlates with declines in safety performance. Financial strain may lead to cuts in safety training, delays in preventive maintenance or a reduction in staffing, which can increase the likelihood of incidents. That is why contractor management programs that monitor financial health in addition to safety metrics can offer better visibility into potential challenges within an organization before they escalate. The importance of this capability lies in monitoring and assurance, enabling organizations and their risk management teams to proactively engage in further reviews and connections with their contracted workforce where needed.

Facility managers: The hidden linchpin

Facility managers have always played a vital role in safety. But their importance grows even more when organizations move beyond compliance. They see the work done, the changes made, the corners being and the systems followed…or not. Their input is essential for:

-

identifying risks

-

identifying and implementing changes

-

monitoring behavior

-

managing supplier safety

FMs are uniquely positioned to see where longstanding or design hazards lead to harm. They can identify patterns, monitor frontline behaviors and advocate for resources that prevent minor issues from escalating into major problems. The workforce they manage constantly needs to adapt, which makes them especially suitable for closing the gap between imagination and reality in terms of actual safety practices.

Empowering the workforce

While leadership sets the tone, frontline workers are the eyes and ears of any safety program. Engaging them meaningfully is not just a good idea, it is fundamental.

This means creating systems where workers are:

-

Trained specifically in SIF risk based on their work environment, including safeguards to prevent fatal injuries.

-

Engaged in a process with leaders to focus, improve and continue SIF prevention strategies. This may include reporting near misses and observations of work practices.

-

Empowered to provide input on procedures that are outdated or difficult to follow.

-

Encouraged to participate in hazard assessments, solution design and improvement.

Implementing these practices moves organizations’ safety practices from a punitive approach based on meeting regulatory requirements to a progressive maturity model, enabling organizational learning, workforce well-being and long-term resilience.

Consistency is key

Consistency is key

Consistency is key, and the best way to achieve consistency is by continually asking the following questions that help reveal if systems are embedded in an organization’s approach and how they can improve:

-

Is work happening like we think it is?

-

Is risk at acceptable levels?

-

How are we improving?

While compliance frameworks can serve as a primary foundation, key systems frameworks, such as those found in ISO 45001 (2018) and ANSI Z-10, leverage well recognized and proven methodologies, including the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle.

This method helps organizations plan — using risk-based information to leverage their resources toward the most important things they should do to achieve success. Organizations have achieved cross-functional innovation with the PDCA model, leveraging it for both systems improvement as well as prioritizing the highest organizational risks to monitor and manage. Here is what this looks like in practice:

-

Plan: Identify serious risks and define the actions needed to address them.

-

Do: Carry out those actions, prioritize the highest risks and document them.

-

Check: Verify whether those actions were practical.

-

Act: Adjust based on lessons learned, then feed that back into planning.

The National Safety Council provides a helpful resource that can further aid in applying the PDCA process to a SIF intervention strategy.

Keep in mind that prioritizing SIF intervention strategies and combining them with a recognized process for continual improvement, such as PDCA, for the entire workforce is especially important in multi-employer environments.

Final thought: Don’t accept the status quo

The increase in workplace fatalities cannot be accepted as the new normal. More than 330,000 lives lost annually in the world is unacceptable in modern economies with advanced safety tools and extensive regulations.

To move the needle, organizations must treat safety as a performance discipline, not just a regulatory obligation. Compliance will always be necessary, but it must be seen as the floor and not the ceiling. Companies that apply systems thinking, invest in cross-functional accountability and empower FMs to lead can build cultures where safety is embedded, measured and continuously improving.

Workplace safety cannot be reduced to a set of posters or slogans. It must be treated as a core operational priority, embedded into every level of operations, leadership and workforce engagement. With this approach, safety is not siloed – instead, it is actively supported by multiple practices and approaches to make it an operational reality instead of an abstract goal.

Scott DeBow, CSP, ARM, serves as the Director of Health, Safety & Environmental for Avetta. With extensive experience in safety management, serious injury and fatality (SIF) intervention strategy and risk-based learning, he plays a pivotal role in driving Avetta's mission to create safe, more sustainable supply chains. DeBow also serves on the Board of Directors for the American Society of Safety Professionals and actively works across multiple industry and professional organizations to advance better practice for safety and health.

Read more on Risk Management and Workplace or related topics Occupant Safety , Risk Management and Training

Explore All FMJ Topics